A Room to Swear In

Delivered August 1st, 2015

First Parish in Belmont,

Unitarian Universalist

(This is a remix of a sermon I delivered in 2001. You can download that original sermon here.)

“There ought to be a room in this house to swear in. It’s dangerous to repress an emotion like that.” –Mark Twain

In August of 2001, I attended the World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerances, held by the United Nations Human Rights Commission in Durban, South Africa. The next month, the World Trade Center was attacked, which made us feel like we hadn’t gotten much done.

I wrote the original version of this sermon soon after I returned home, to New York City, to be delivered at the Unitarian Society of Hartford. In fact, I mostly wrote it the night before I delivered it. I was up all night in the guest room of the lovely people who were putting me up, typing away at my little laptop. I staggered out in the morning, sleepless but done, only to discover my hosts only had decaf. They also didn’t have a printer (I was younger and not great at planning), nor could they find one I could use in town, so I delivered the sermon, caffeine-deprived, from my laptop, which I propped up on the pulpit in front of me. I’ll post the original on my website later, for those of you interested in comparing and contrasting.

I had plenty of coffee this morning, though I did stay up a bit late, and then got myself up early, so I could fully rework this. A lot has changed since 2001. We were then only at the beginning of what would be a catastrophic 8 years under the Bush administration, with no idea of how much we would see dismantled and rolled back. We also didn’t know yet about the improbable, then inevitable election of our first African-American president, the seemingly unflappable President Obama.

But even in the time between when I was asked to give this sermon here, and now, there has been immense change. I sent my original version of this to David in January, after he delivered a sermon with a similar metaphor. He asked if I would consider delivering it this summer. This was only a month or so after the protests in Ferguson, MO which birthed the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Initially a reaction to the lack of accountable in the Ferguson police force over the killing of Michael Brown, the movement was soon protesting the deaths of other unarmed Black Americans at the hands of the police, among them: Eric Garner, Tamar Rice, John Crawford III, Walter Scott, Sandra Bland, Samuel DuBose.

And, of course, we’ve seen the horrific killing of nine Black Americans, shot in their church by a young man they welcomed into their prayer circle. I have been welcomed into Black churches, and experienced the disciplined open-armed Christian love practiced by their members toward me, a White person. There is an element of self-preservation in the choice to be kind and welcoming, but it also comes from a deep spiritual base. If nothing else, the shootings in Charleston gave lie to the tiresome scolding of respectability politics, proving, yet again, that the killing of Black people has little to do with how they behave with White people.

This sermon is about White people. I’ve joked that I should have titled it Honkies. Let’s pretend from here on out that I did. This sermon is about honkies.

I attended the UN Conference Against Racism on behalf of the Unitarian Universalist United Nations Office as part of a delegation of five delegates from the Unitarian Universalist Association. We all stayed in the same B&B.

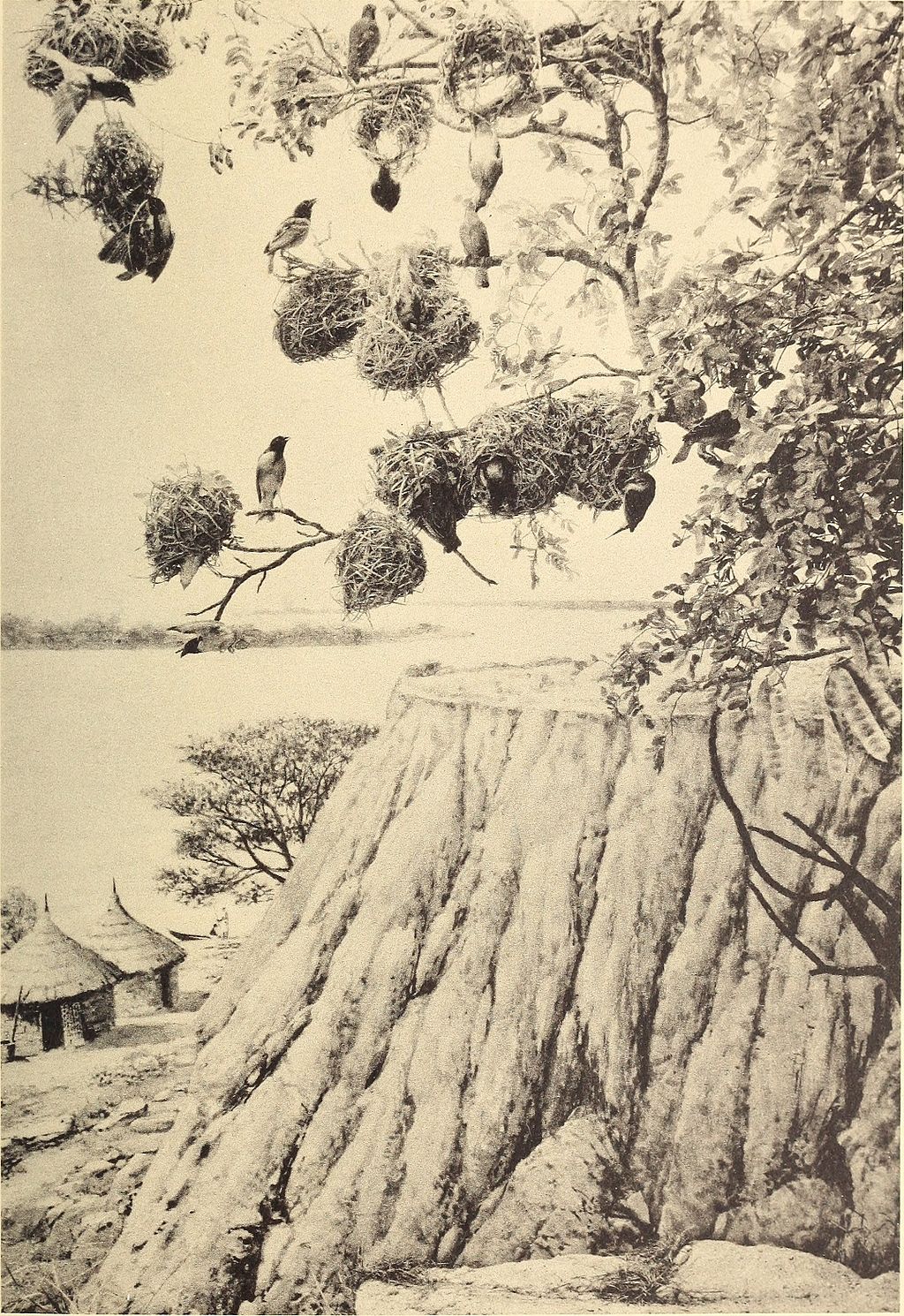

Every morning we would breakfast together on the tiled patio of this stunning, if a bit gone-to-seed, B&B, with views of the ocean stretching before us. One morning, the sun was shining. This was unusual. South Africa was just coming out of Winter, so the days were often dark and cold and drizzly. At the back of the patio was a tree absolutely filled with the nests of Weaver birds, hanging down, clinging to the branches. I decided to sit out in the sun for a while and watch the Weaver birds.

The Weaver birds, as you might guess from their name, weave their nests. They pluck long palm fronds and weave them together with their beaks, poking and pulling. It’s a fascinating process to watch, and I spent some time at that. The birds were flying around, lemon yellow feathers gleaming, zipping back and forth between the palms and the nests, frantic. These were the male birds, you see, and spring was springing. Soon, the female birds would be coming by, to check out the nests. If the males wanted to mate, they’d better weave, but fast. So the beaks pulled and poked, pulled and poked.

Clearly, this was how humans had learned to weave baskets, from sitting and watching this.

You see a lot of baskets in South African cities. Not in use, but for sale. Women sit on blankets on the sidewalk, or on the boardwalk by the ocean, and they sell baskets. Baskets made from reeds, and fronds and electrical wire, of different colors and shapes and patterns.

But you wouldn’t see a basket for sale that looked like one of the weaver birds’ nests. While the nests are naturally beautiful, they would be considered sub-par if made by a human. They are slightly misshapen, and the fronds stick out every which way. The female weavers don’t care, they just want a safe place for their eggs. As humans, however, we took the weaving concept and ran with it. Not only did we need to improve the design, creating baskets that were so tight they could hold water, or evenly meshed enough to sort grains, but we needed the baskets to look good. We added patterns, and figures, we recorded stories, right in the weave of the basket.

This is the human need for order.

And I use the word “need” very intentionally. Without order, the human race would not have survived. We have few natural defenses, and our ability to organize has allowed us the opportunity to create safety and stability for ourselves.

It was a funny coincidence that the first request for my sermon about the World Conference Against Racism should come from Hartford. Before I’d left for the conference, I’d thinking a lot about the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which was written in that very town. Like another writer associated with Hartford, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Twain sought to address the injustices of slavery but unlike Stowe, he did not seek to write a purely political book. In fact, before the book starts, he writes the following notice:

“PERSONS attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot.”

Lucky for me, Twain is long dead, and unlikely to carry out his threats.

Huck Finn is a really uncomfortable book. Like the Adventures of Tom Sawyer, it takes place in the fictional St Petersburg, Missouri, based on Mark Twain’s hometown of Hannibal, Missouri — which lies just 100 miles north of Ferguson, Missouri, as it turns out.

While the Adventures of Tom Sawyer puts a winking gloss on childhood shenanigans, Huck Finn gets dark and complicated. It is, to use an academic phrase, problematic. Part of this lies in how it is told. Tom Sawyer is written in third person, with the benefit of narrative explanation and justification. Huck Finn is written in first person. Huck is telling us the story, and he doesn’t hide his thoughts.

At the very beginning of the book, Huck has decided to return to the Widow Douglas’ house, after running away before, because Tom says Huck can’t be in his “band of robbers” unless he goes back. But life with the Widow is hard for Huck:

“She put me in them new clothes again, and I couldn’t do nothing but sweat and sweat, and feel all cramped up. Well, then, the old thing commenced again. The widow rung a bell for supper, and you had to come to time. When you got to the table you couldn’t go right to eating, but you had to wait for the widow to tuck down her head and grumble a little over the victuals, though there warn’t really anything the matter with them – that is, nothing only everything was cooked by itself. In a barrel of odds and ends it is different; things get mixed up, and the juice kind of swaps around, and the things go better.”

Huck becomes more comfortable with the widow’s way, but then his father returns and turns it all upside down again. Which happens a lot in Huck’s life. Which is why he’s not like Tom, confident, cocky Tom. Tom’s childhood doesn’t get rocked by these things. He creates the Band of Robbers for a little excitement, but Huck ends up disappointed because all of the robbing and crime is in Tom’s imagination. Except for the occasional turnip.

Then when Huck escapes from his father, after the courts have failed him and he ends up in the custody of this man who is least safe for him to be with, he becomes dependent on stealing, and disguises and trickery. This Civilization is all well and good for the Widow, and for Tom and Judge Thatcher and Miss Watson , but it doesn’t seem to be working for Huck. Nor is it working for Jim, who has been a slave since birth, and has escaped as well, and is heading down the river with Huck.

Yet he and Huck have long conversations about the morality of what they are doing. The rules of the civilization they observe from the outside tug at them, even while they see the flaws.

And it was wrong, what they were doing. It was against the law. Jim was property that Huck was stealing.

Huck had chosen to live outside the confines of Missouri civilization, though he knew it would be safer and easier to be on the inside.

Jim, however, has no chance of being on the inside. Only Huck does. Huck can renounce his wildness and be admitted, because he can be White. Huckleberry Finn. He’s Irish.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was written in 1885, but is taking place around the late 1840’s. A time when the Irish in America were being courted by the slave states as allies. The Irish were considered as low as dogs by the English, but now in America they were going to get to be part of the club. The White club.

In this country, some of us get to be White. Which has been primarily defined as being “not Black” There were rules we’ve had to follow since the Jazz Age: we don’t have rhythm, we don’t dance “dirty”, we clap on the 1 and 3 instead of the 2 and 4. But the White clothes get itchy and they don’t always fit right. Little Richard sold more records than Pat Boone, Elvis’ pelvis was still moving beneath the edge of the TV screen, white girls were carried out of Beatles concerts on stretchers, weak from syncopation and sex appeal.

The “Civilizing” didn’t work.

In the meantime, we were telling Black people, and really believing, that everything would be fine for them if they just acted civilized like us.

One of the parts of our human need for order is our need for social order. One of the things that was made most clear at the UN Conference is that every society has not only a bottom rung, reserved for a particular group of people, but also a whole middle order, kept mollified about their varying lack of power by the reassurance that they are at least not at the bottom rung.

The New York Times, back in 2001, before the Conference started, dismissed it in its editorial pages as useless because it was going to be “messy”

I laughed when I saw that. Messy??? Of course! How could any attempt to address Racism as a global issue not be messy? Racism is messy. The order we have falsely imposed on humanity has created a mess. Not that messy has to be bad. The nests of the weaver birds are messy. But they are strong. They can hold and cushion the eggs.

The basket that we’ve created lets a lot of eggs drop.

Do we always need to have outsiders? Can we build a basket to hold all the eggs? Let’s not worry right now if the basket is messy, let’s just make it strong. Then we can make it beautiful.

After the riots in Ferguson, the comedian Chris Rock gave an amazing interview to New York magazine. When they asked him about the riots, and the nascent #BlackLivesMatter movement, he said:

“When we talk about race relations in America or racial progress, it’s all nonsense. There are no race relations. White people were crazy. Now they’re not as crazy. To say that black people have made progress would be to say they deserve what happened to them before. So, to say Obama is progress is saying that he’s the first black person that is qualified to be president. That’s not black progress. That’s white progress. There’s been black people qualified to be president for hundreds of years...The question is, you know, my kids are smart, educated, beautiful, polite children. There have been smart, educated, beautiful, polite black children for hundreds of years. The advantage that my children have is that my children are encountering the nicest white people that America has ever produced. Let’s hope America keeps producing nicer white people.”

Let’s be nicer White people.

We are all weaving this basket. It ain’t pretty, it ain’t strong enough yet. Some of us know that more than others. But it’s better than it was. Let’s get better at weaving. Let’s weave the basket tight enough and big enough to hold all of us.